Hello there, Noam here. Having a good day/night? Today, I am sharing a story from 1955. I hope you find it as interesting as I do. As always, please share any thoughts or comments.

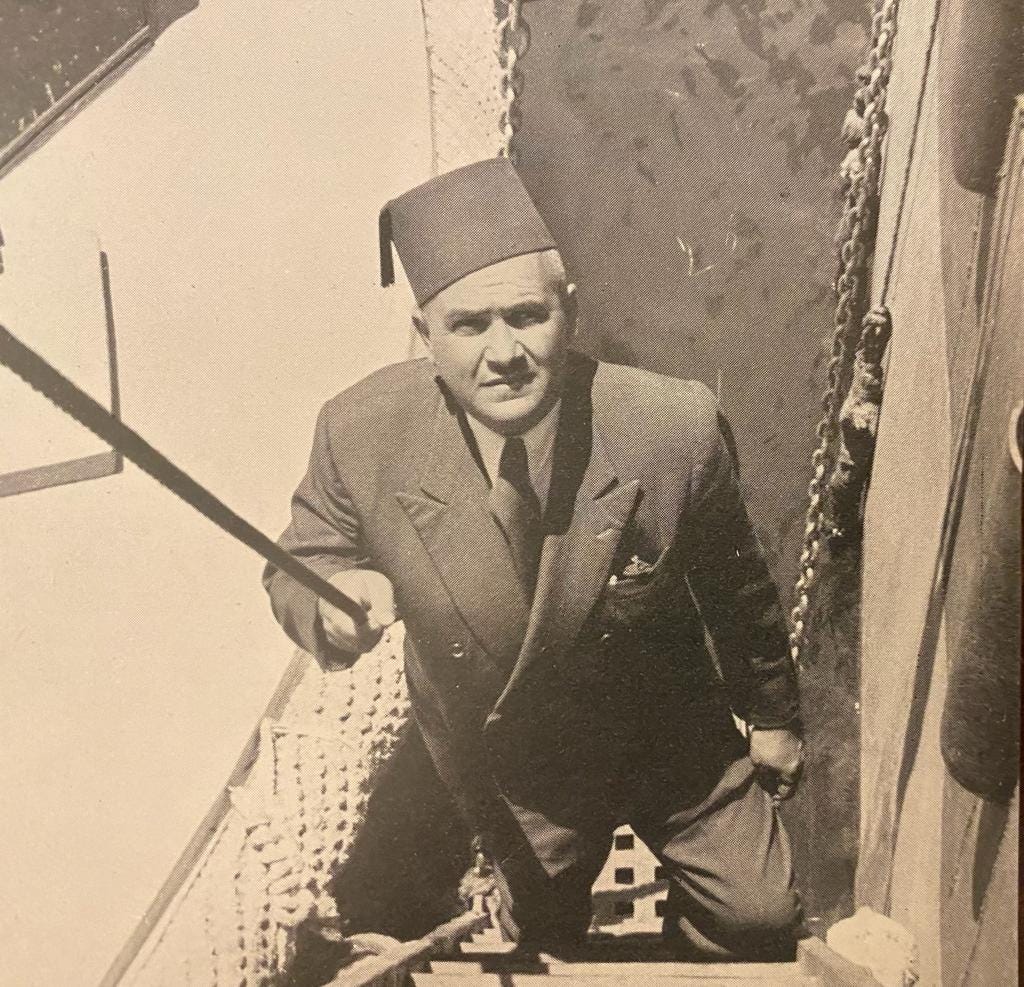

He never believed in using tugs to help pull large vessels in and out of the Port of Beirut. He was known in maritime circles as the “full-ahead, full-astern” pilot. Hundreds of sea captains approaching the port expected to greet him and his boat. His name was Radwan Baltaji, and he was the chief pilot of Beirut.

Baltaji grew up in the port in the early years of the 20th century. His name later turned into a by-word for mastery among commanders of various nationalities. Based on an Iraq Petroleum magazine article from October 1955, here is his long-forgotten story1.

The Chief Pilot

Radwan Baltaji had a routine of a disciplined mind: he used to go to bed every night at eight and rise at four every morning. His daily duties included waiting for news about a vessel’s arrival to the Port of Beirut in Lebanon.

Radwan and his brothers, Mahmoud and Salah, would take turns in joining a ship when it was “lying three miles out from the breakwater.” Once any of the three pilots was on board the vessel, he would head to the bridge and take over command to berth the ship. Their work was done in collaboration with the harbormaster and the shipping agents at the port.

At the Beirut port, ship commanders expected tugs. Radwan, however, had an “aversion” to tugboats. “My father never used a tug in his life, and neither have I,” Radwan said in 1955.

The maritime industry has grown and changed exponentially since then. Tugs are powerful boats used in the berthing operations of ships. According to a post on Marine Insight, a “tugboat eases the maneuvering operation of vessels by forcing or tugging them towards the port. Mega vessels can never be maneuvered by their own. Also, with the increased size of the boat, they need tugboats to carry some of their domains and tow them through narrow water channels.”

Radwan’s disapproval of tugboats left some commanders nervous, including the commander of a 38,000-ton American aircraft carrier, which was the “largest vessel Baltaji [had] ever brought into Beirut harbour,” according to the magazine.

“Where are the tugs?” the commander asked when Radwan joined the ship one day. “There will be no tugs,” Radwan responded. Then he took charge of berthing the big ship:

“Baltaji allowed the big ship to edge into the narrow harbour, then he dropped the starboard anchor and increased speed to 18 knots. As he stopped engines, the great ship swung gently alongside her moorings. The commander was alternately confused, confounded, and delighted; it was the first time he had ever seen such a thing done in so confined a space,” reported the Iraq Petroleum.

The ‘Gallant Little Mooring Launch’

Radwan was the son of Ibrahim Baltaji, who reportedly advised on the location of the Port of Beirut “when the French obtained the necessary concession from the Sultan of Turkey” and served aboard foreign ships in the Mediterranean. During the First World War, Ibrahim was appointed chief pilot to the British Navy at Beirut2, according to Iraq Petroleum. Radwan came from port royalty.

Radwan began his work at the port at the end of the war. To some Lebanese, his name is synonymous with the French luxury liner, Champollion, which ran aground amid severe weather conditions just south of Beirut in December 1952. The ship was powerless in the face of a raging storm that rendered rescue operations impossible. Hundreds of people decided to jump off the ship and swim towards the Lebanese shore. It was in those desperate hours when rescue came from Beirut.

Using two boats, Radwan, his two brothers, and his cousin Rizk helped transport passengers to safety. Radwan’s “gallant little mooring launch”, according to Iraq Petroleum, “brought ashore no less than 168 survivors.” The story of the Champollion and the Baltajis’ operation was covered in 2020 in an article published by Lebanese news website Al Modon, and also in 2021 by Beirut Heritage and the website 961.

In addition to the Champollion, Radwan endured several wartime incidents that required his skills and knowledge. These included a Norwegian tanker that Radwan rescued on a stormy night as the vessel struggled to avoid running aground after losing its starboard anchor. Another involved a Dutch tanker that was torpedoed outside Beirut. Abandoned by its crew, the burning ship was driven ashore and was destined to blow up. Here is the full story:

“Radwan Baltaji came up alongside her in his mooring launch- her propellers were still turning—and, despite the fact that she might blow up at any moment, went aboard to satisfy himself that nobody had been left behind. He then withdrew to his launch, but he took with him the captain’s cap and binoculars which he had found on the bridge. Back at the base he expressed the view that the ship could be saved and, when he was told in no uncertain terms that nobody could assess such a situation without going on board— which was surely impossible— he produced the cap and binoculars. The following day the fire was extinguished, and the ship was towed into Beirut harbour. A valuable tanker was thus saved at one of the most highly critical stages of the war.”

The ‘Secret Ambition’

By 1955, Radwan had brought in around 25,000 vessels. He saw vessels of different types, yet there was one particular ship he had hoped to bring into the port before retiring: an atomic (nuclear-powered) ship3.

The port and the people running it have unfortunately changed since Radwan’s time.

On August 4, 2020, a massive explosion at the port killed over 200 and wounded more than 6000 people. The blast was linked to a substandard ship, the Rhosus, which was allowed to enter the country on at least two different trips in 2013. On its last trip to Beirut, it was carrying a hazardous cargo of ammonium nitrate. The highly explosive material was unloaded and stored in unsafe conditions at a warehouse until it blew up.

Despite the devastating blast, substandard ships continue to find their way to Lebanese ports. For more on this, read my investigation, The Cruel Ships, which I published on July 15.

Iraq Petroleum was the magazine of the Iraq Petroleum Company (IPC), which had a monopoly over Iraqi oil production. ExxonMobil, BP, Shell, and Total used to own the IPC before Iraq nationalized it in 1972. (Source: Iraq and the Politics of Oil: An Insider’s Perspective, by Gary Vogler, 2017). Back in 1955, when the article was published, Iraqi crude oil used to reach the Mediterranean. The Kirkuk-Baniyas pipeline was opened in 1952, and before it there was the Kirkuk-Haifa pipeline.

Radwan also became chief pilot to the British Navy at Beirut during his time.

In 1953, the United States – which in 1945 dropped two atomic bombs on the Japanese cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki, killing hundreds of thousands of people, mostly civilians— initiated a PR campaign to persuade the world about the civilian use of nuclear energy. The US built the N.S. Savannah, which was the world's first nuclear-propelled merchant ship, according to a report by the BBC. In 1964, the vessel toured Europe, in a sort of diplomatic mission. But of course, the ship and the few other nuclear-propelled merchant vessels that were built in a few other countries, failed to convince the world that nuclear-energy was the future. For more, read “The ship that totally failed to change the world” by Tammy Thueringer and Justin Parkinson from the BBC, July 25, 2014: https://www.bbc.com/news/magazine-28439159